Award-Winning!

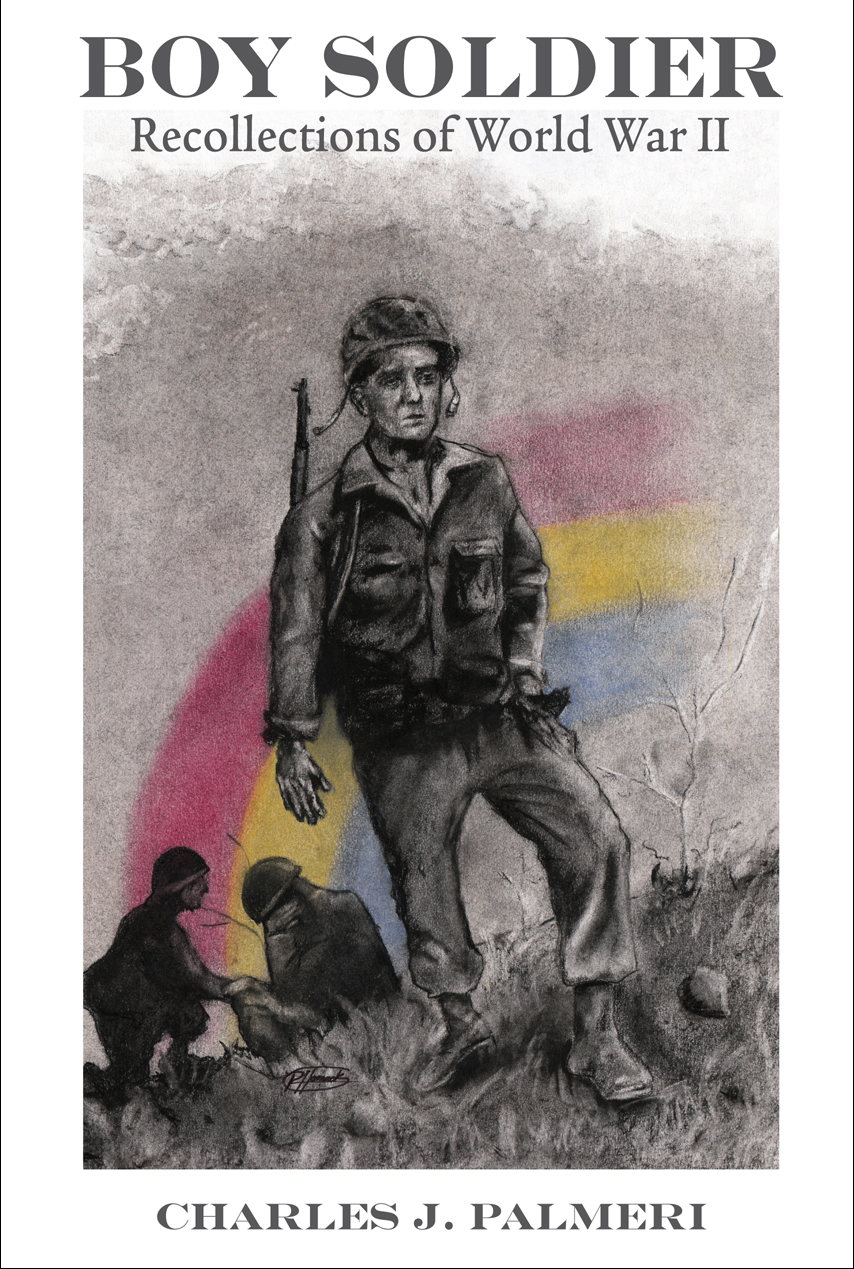

Boy Soldier

Recollections of World War II

by Charles J. Palmeri

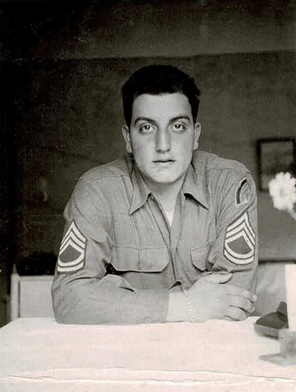

Boy Soldier: Recollections of World War II, Charles Palmeri’s account of his experiences as a member of the 42nd Infantry, Rainbow Division, Company L, is that of an eyewitness, full of drama and pain. Now, at the age of 93, Charles remembers the perils and heartaches of World War II, recounting the dangers, the friendships, the horrors of the Dachau concentration camp, and then his post-war command of Camp Marcus W. Orr, an internment camp for civilian Nazi sympathizers.

For the student of world history who is interested in hearing first-hand from the pen of a man who was actually there, Boy Soldier: Recollections of World War II is the compelling, must-read story of an American teenager who becomes a real leader both during and in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

Eyewitness to History

When Buffalo native 18-year-old Charles J. Palmeri arrived in France as a brand new member of the 42nd Infantry, assigned to the 232 Regiment, Company L, he was among thousands of “replacements,” young men who would bolster the depleted ranks of the 42nd, which had sustained losses of approx. 50 percent of its fighting force. In the next 100 days, the 42nd “Rainbow Division” would lose another 50 percent of its men in some of the most violent fighting of the Second World War, as the new “replacements” found themselves pitted against battle-hardened Nazi troops. And then, in the waning days of the war, the 42nd would arrive at the gates of hell: Dachau, the infamous Nazi concentration camp.

Join Charles as he takes you inside the U.S. Army, just as the war was drawing to its conclusion, in Boy Soldier: Reflections on World War II, his riveting memoir. Meeting new friends and fighting fanatical foes, Charles finds that heavy responsibilities have been thrust upon him, even though he is still in his teens. Read about what Charles saw, and what he thought about what he saw, in Boy Soldier.